Witnessing the Siege of Boston

In this primary source set, students will engage with a variety of letters, maps, artifacts, and more to explore diverse Bostonian experiences at the outbreak of the Revolutionary War.

Inquiry Question 1: How did ordinary Bostonians experience the Siege of Boston? What were their fears and concerns?

Inquiry Question 2: How did factors like class, gender, race, or political views affect people’s experiences?

Source Set

Download Source Set

Glossary

Civilian:

in a war, a person who is not a member of the armed forces

Siege:

a military operation in which an army tries to capture a town by surrounding it and stopping the supply of food, etc. to the people inside

Occupation:

moving into a country, town, etc. and taking control of it using military force; the period of time during which a country, town, etc. is controlled in this way

(Military) Lines:

a row or series of military defenses where the soldiers are fighting during a war

Blockade:

Surrounding or closing a place, especially a port, in order to stop people or goods from coming in or out

Barricade:

a line of objects placed across a road, etc. to stop people from getting past

Learning about the Siege of Boston:

As you analyze the sources in this set, consider the following questions:

What type of primary source is this?

Who created it?

When was it created?

Who was involved?

What was its purpose?

How does it help us understand how ordinary Bostonians experienced the Siege of Boston?

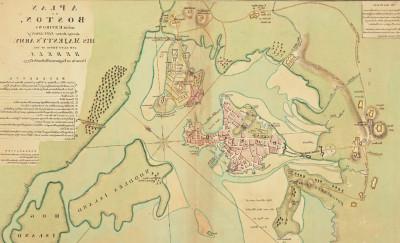

This map of the Boston area published in London in 1776 was based on a drawing made in October 1775 by Lieutenant Richard Williams, an officer in the Royal Welsh Fusiliers (but not, as the map states, a trained engineer). Oriented with north toward the upper right, this plan was drawn by and for British use and refers to the American militia as the "Rebels." The map includes points of military interest such as batteries and fortifications; the locations of prominent sites (Copps Hill, Faneuil Hall, Boston Common, the Boston Wharf, Bunker Hill, Roxbury Meeting House); roads, hills, nearby islands in Boston Harbor and the area exposed at low tide. The map also clearly shows how Boston Neck was the only entrance and exit to the city by land at this time, and how Boston Town was cut off from the “country” by barricading the Neck during the siege.

Citation: A Plan of Boston, and its Environs shewing the true Situation of His Majesty's Army, Map, London: Andrew Dury, 1776. Map depicts Boston in October 1775. Massachusetts Historical Society, http://mdj.imtiazqazi.com/database/2053.

Miss Ellery resided with her mother in Charlestown at that time, and on the morning of that memorable day the servant handed her the spoons which had been used at breakfast, which in the excitement of the time, she immediately put in her pocket. As the firing on the town increased, Mrs. Ellery was advised to leave the scene of the tumult, and with her daughter accordingly walked out toward the country, and found shelter in one of the neighboring towns. Of all their household goods no relic was left but the few spoons that were in Miss Ellery’s pocket …

-Anna Sophia Tileston Everett (Relief Ellery Vincent’s great niece), upon donation of the spoons to the MHS in 1907

Miss Relief Ellery (later Ellery Vincent), a 20-year-old Charlestown resident, took these silver spoons from the breakfast table as she ran out the door on the morning of 17 June 1775, fleeing to the woods as the British began firing on her town during the Battle of Bunker Hill. When she returned, her entire home was gone. The spoons were all she had left.

Citation: Teaspoons belonging to Relief Ellery, Silver by John Allen, [17--] Made in Boston, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://mdj.imtiazqazi.com/database/3514.

Read an excerpt of Deming's account.

Read a simplified excerpt.

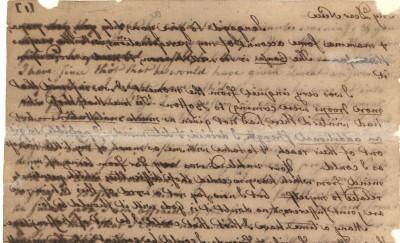

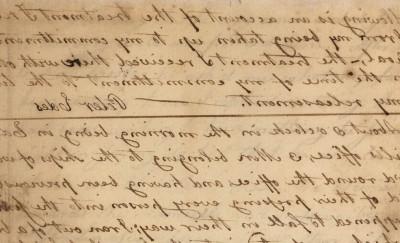

Early on Wednesday the fatal 19th April, before I had quited my chamber, one after another came running up to tell me that the kings troops had fired upon & killed 8 of our neighbors at Lexington in their way to Concord...I went to bed about 12 this night having… resolv'd to quit the town before the next setting sun, should life, & limbs be spar'd to me. Towards morning, I fell into a sound sleep from which I was waked by [my husband]... informing me that I was Genl Gage's prisoner -- all egress, & regress being cut off between the town & country... No words can paint my distress…

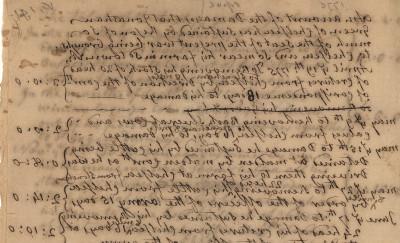

Within this 12-page letter written in the form of journal entries from 15-26 April 1775, Sarah Winslow Deming transmits news of the Battle of Lexington and Concord and the first few days of the Siege. Her account describes the fear in the town and her escape from Boston on 20 April 1775, and the rumors of violence that swirl as she flees the city. There are two excerpts for this document: in the first, Deming conveys the frightening atmosphere in Boston during the initial occupation, and the second details her flight from Boston as she travels through various locations including Roxbury Hill, Jamaica Plain, Dedham, Providence RI, and eventually lands in Connecticut. This letter also reveals the experiences of Lucinda, a woman enslaved by the Demings, as she also travels on this journey from Boston.

Citation: Sarah Winslow Deming journal, 1775, On deposit from the Historic Winslow House Association, Marshfield, Mass. Reproduced with permission, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://mdj.imtiazqazi.com/database/1898.

Read excerpts of Andrew's letters to Barrell.

Read simplified excerpts.

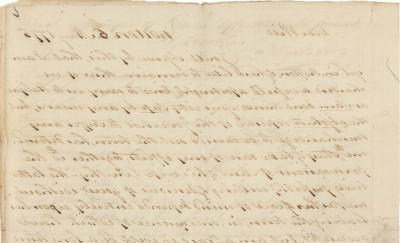

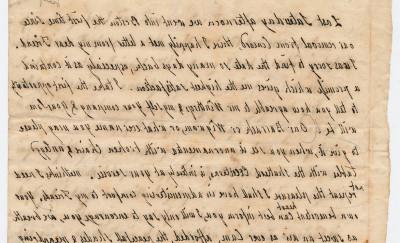

I expect to bid farewell to Sam & his wife & Ruthy, tomorrow or Sunday, but I hope not an eternal farewell - you can have no conception, Bill, of the distress the people in general are involvd in, you'll See parents that are lucky enoh to procure papers, wth bundles in one hand & a string of children in the other, wandering out of the town (wth only a Sufferance of one days provision) not knowing whither they'll go.

In this letter written to his brother-in-law on 6 May 1775, John Andrews describes conditions in Boston shortly into the Siege. Andrews mentions the large number of people trying to get a permit allowing them to leave Boston, and how difficult it is to find fresh food and supplies. As he closes the letter, Andrews says that his wife (Barrell's sister) Ruthy is preparing to leave as well, but that Andrews will be staying behind to protect their home and property.

Read his following letters from 1 June 1775 and 11 April 1776.

Citation: Letter from John Andrews to William Barrell, 6 May 1775, From the Andrews-Eliot correspondence, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://mdj.imtiazqazi.com/database/2049.

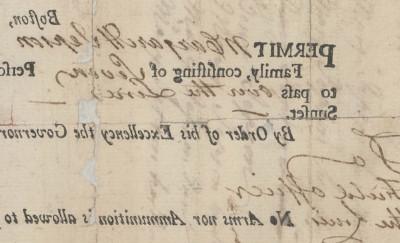

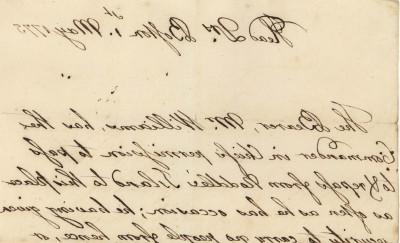

See full transcription of handwritten text.

This permit, issued by General Thomas Gage, gives permission to the holder Margaret Jepson and her family (names listed on the back) to enter or exit Boston without harm while the town is occupied by British soldiers following the battle of Lexington and Concord. 12,000-13,000 people flee Boston as a result of this agreement. For further reading, see a broadside announcing this arrangement.

Citation: Permit to pass through British lines, May 1775, Issued by Thomas Gage, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://mdj.imtiazqazi.com/database/527

This pass authorized Henry Howell Williams unlimited access both to Boston and his home on Noddles Island after the start of the Siege of Boston under the condition he "carry no people from hence, or bring any thing off the Island." It is worth noting that while Williams needed a pass to travel in and out of British-controlled Boston, his “servants” (potentially indentured servants or enslaved people) did not need their own passes. You can see Noddles Island and Williams’ house on the map of Boston in this source set.

Citation: Pass issued on behalf of Rear Admiral Samuel Graves to Henry Howell Williams allowing access to Noddles Island, 1 May 1775, From Noddles Island papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://mdj.imtiazqazi.com/database/1912.

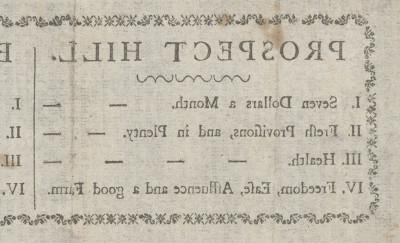

This handbill is an early example of American Revolutionary War propaganda. The handbill compares living conditions for soldiers on both sides of the lines during the Siege of Boston, 1775-1776, claiming that colonial forces enjoyed things like “Fresh Provisions, and in Plenty” while British soldiers only had “Rotten Salt Pork.” It was printed to encourage British soldiers to desert the British army and join colonial forces camped just a mile away behind the fortifications on Prospect Hill in Cambridge, in full view of the British troops on Bunker's Hill. On the back of the handbill is a message from an “old soldier” encouraging British troops to refuse their orders to kill colonists, fellow “sons of Englishmen.”

Citation: Prospect Hill, Bunker's Hill, Handbill, [Cambridge or Watertown, Mass. : unidentified printer, 1775?] Massachusetts Historical Society, http://mdj.imtiazqazi.com/database/534.

Read an excerpt of Green's account.

… & in the months of August September & October to damage he Sustained by 80 soldiers taking away & Devouring his apples & pears…

Jonathan Green (1719-1795) was a farmer in Chelsea, MA. Green's property along Boston Harbor faced Charlestown, a location that got the attention of both the British and American troops. During the Siege of Boston, Green moved much of his livestock inland to Stoneham to protect it from British soldiers. However, both British and American troops stole Green’s crops and damaged his remaining property. In this 2-page account, Green describes the harms he suffered, and lists how much money the loss of crops and property damages cost him.

Citation: Account of damages done to Jonathan Green during the Siege, [7 May 1776] From Volume V of the Chelsea (Mass.) papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://mdj.imtiazqazi.com/database/1911.

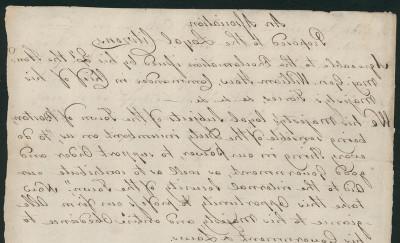

Read an excerpt of Howe's Proclamation Proclamation.

We his Majesty's loyal Subjects of the Town of Boston, being sensible of the Duty incumbent on us, "to do everything in our power, to support Order and good Government, as well as to contribute our Aid to the internal Security of the Town." Now take this Opportunity to profess our firm Allegiance to his Majesty, and entire Obedience to his Government & Laws.

British General William Howe faced a number of difficulties in keeping control of Boston during the winter. Howe knew that supply routes from the ocean would soon be cut off by winter storms, and they would quickly run low on food and firewood. While many patriot families had left Boston, the city was crowded with loyalist refugees seeking protection from the British Army. On October 28, 1775, Howe issued a proclamation requesting that the people who remained in Boston either enlist in or offer aid to the British army. To the proclamation Howe attached a letter (pages 3-4) from “his Majesty’s Loyal Subjects of the Town of Boston” who supported his proclamation and agreed to help him as best they could.

Citation: Proclamation by General William Howe (manuscript copy), 28 October 1775, From Miscellaneous Bound Manuscripts, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://mdj.imtiazqazi.com/database/532.

Read an excerpt from Edes' diary.

...We are very close confin'd, having the door open Sometimes one hour in 24, and Sometimes not at all...

In this diary, seventeen-year-old Peter Edes recorded entries about his capture and his three and a half month imprisonment in a sweltering Boston prison during the Siege. Edes was an apprentice printer and the son of Benjamin Edes, a journalist, printmaker, and member of the Sons of Liberty. Peter Edes wrote about the harsh conditions he and other prisoners experienced and the uncertainty of his situation. He comments often on swearing and foul language used by his jailers. The last page of the diary is a list of 30 prisoners taken from the Battle of Bunker Hill and in his entry of 21 September 1775, Edes mentions that only 11 of them are still living.

Citation: Peter Edes Diary, June-October 1775, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://mdj.imtiazqazi.com/database/1978.

Read an excerpt of Winthrop's letter.

And a simplified excerpt of her letter.

Our [home], when you see it unornamented with broken chairs & unleggd tables with the shatterd Etcetteras, is intirely at your service. methinks I need not repeat the pleasure I shall have in administering comfort to my Friends[...] What an unexpected Blessing! the change from the din of arms & the shrill Clarion of war.

Hannah Winthrop lived in Cambridge, MA, where her husband John Winthrop taught mathematics and natural philosophy at Harvard. The Winthrops were patriots, and during the Siege of Boston they left Cambridge and relocated to Concord, MA. In this letter, Hannah Winthrop writes to her friend Mercy Otis Warren, a well-known poet, historian, and patriot. Winthrop describes returning home following the end of the Siege. Although her home suffered some damage during the British occupation, Winthrop describes how peaceful Cambridge is following the departure of British troops. However, she also describes an ongoing smallpox outbreak in Boston.

Citation: Letter from Hannah Winthrop to Mercy Otis Warren, 8 July 1776, From Correspondence with Mercy Otis Warren, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://mdj.imtiazqazi.com/database/3344.

For Teachers

Ordinary Civilians and the Siege of Boston

Background Reading

-

Historical Overview: Ordinary Civilians and the Siege of Boston

-

The Siege of Boston was an 11-month period during which American militias contained British troops within the city of Boston and, after the Battle of Bunker Hill, to the Charlestown peninsula. The occupation began when British soldiers retreated to the city on April 19th 1775 after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, and ended on Evacuation Day on March 17th 1776. During the siege many residents moved out of Boston, and some Loyalists from the surrounding countryside moved into the city. Conditions within Boston were harsh for all who remained; although the British maintained control of Boston Harbor, provisions dwindled while they waited for supply ships to arrive. Residents faced violence from soldiers and from the battles taking place nearby, including the Battle of Bunker Hill where the neighborhood of Charlestown was burned down. It became difficult to find fuel and food, and supplies grew more expensive as the siege dragged on. Those that did leave Boston found themselves as refugees searching for a place to stay, and risked their homes and belongings in Boston being stolen or destroyed.

These articles offer additional historical background and details of events during the Siege of Boston: Anxiety and Distress: Civilians Inside the Siege of Boston by Alexander Cain, Journal of the American Revolution; and The Siege of Boston, by Adam E. Zielinski, American Battlefield Trust.

Essential Questions

- Inquiry Questions for Primary Source set

-

As students examine each of the documents in the set have them consider:

- How did ordinary Bostonians experience the Siege of Boston? What were they worried about or afraid of? What were their biggest concerns? What choices did they make?

- How did factors like class, gender, race, or political views affect people’s experience of the Siege of Boston?

- How did the geography of Boston in 1775 play a role in the siege? Where did people live? How did they enter and leave Boston, and what borders and boundaries did they pass through? How was Boston in 1775 similar or different to the Boston we know today?

Close Reading Questions

-

Questions for each document in the source set

-

- Look at the title of this map. What does it tell us about the mapmaker and why they made this map?

- How was the geography of Boston in the 1700s similar and different to Boston today?

- Extension opportunity: compare to a modern map of Boston.

- During the Siege of Boston, how would people enter and exit the city? What difficulties did they face? How would food and supplies get to the city?

- Look at the legend (labeled Reference). What places did the mapmaker highlight in the legend? Why do you think these places were important to the mapmaker?

- Look for 3 places that the map shows information about the British or colonial armies. What do they tell us about the Siege?

Teaspoons belonging to Relief Ellery

- Why do you think Relief Ellery kept these spoons?

- Why do you think these spoons are in the MHS archive?

- Look for Charlestown on the Plan of Boston and its Environs map, and look at the Siege of Boston timeline (specifically the events of the Battle of Bunker Hill). Can you find Charlestown on the map? What does the map show in and around Charlestown

- Relief Ellery’s great niece tells us that a servant handed the spoons to her before they left the house. This person may have been a paid or indentured servant, or they might have been enslaved by the Ellerys. What do you think the attack on Charlestown might have been like for this person?

Sarah Winslow Deming journal, 1775

- What is Sarah Winslow Deming afraid will happen in Boston after the Battle of Lexington and Concord?

- What are some words she uses to describe her emotions?

- Why is it difficult for Deming to leave Boston at first? What challenges does she face?

- Extension: Look at the Plan of Boston and its Environs map and see where the British lines are blocking entrances and exits to Boston

- Deming travels through a number of locations in Massachusetts during her escape from Boston. How many towns and cities can you name?

- Deming hears a lot of rumors about what is happening in Boston, and it is difficult to figure out what is true. What is one of the rumors she hears during her travels?

- The Deming family enslaved a woman named Lucinda, who is taken with them on their escape from Boston. How does Lucinda experience the journey? What are some of the ways she is treated differently from Sarah Winslow Deming and the other white people she travels with?

Letter from John Andrews to William Barrell, 6 May 1775

- Why does Andrew decide to stay in Boston? Why does his son Sam and his wife Ruthy leave?

- According to Andrews, what is it like trying to get a pass to leave Boston during the beginning of the Siege? See these two examples of these passes giving permission to cross through the British lines in and out of Boston during the Siege.

- What does Andrews say about getting food during the Siege?

- What is Andrews’ “most earnest wish and prayer?”

- Why does Andrews worry that his goodbye to his son and wife might be “an eternal farewell”?

Permit to pass through British lines, May 1775

- What did this pass allow the holder (Margaret Jepson) to do?

- Why do you think that “arms and ammunition” were not allowed to pass through the British lines? Why not “merchants” either?

- Look at the Plan of Boston and its Environs Can you find the British “lines” that the pass allowed people to travel through?

- Compare this pass to the British Military Pass Issued to Henry Howell Williams. How are they similar or different?

British Military Pass Issued to Henry Howell Williams

- What did this pass allow the holder (Henry Howell Williams) to do?

- Look at the Plan of Boston and its Environs. Can you find Williams’ home on Noddles Island? What happened to it?

- The pass says that says that Williams may bring “no people” with him to or from Noddles Island, but also said that Williams’ “own servants row him.” Why do you think that the British didn’t make the servants (possibly enslaved people) have their own passes?

Prospect Hill/Bunker’s Hill Handbill, 1775

- Who created this handbill and why?

- What does it say that colonial soldiers have on Prospect Hill in comparison to British soldiers on Bunker Hill?

- What are some of the words this handbill uses to convince British soldiers to desert the British army?

Account of damages done to Jonathan Green during the Siege, 7 May 1776

- What does Jonathan Green say is the reason that his property was damaged?

- Give five examples of things that Green says were damaged or stolen. Does anything surprise you?

- Compare this ledger to the Letter from Hannah Winthrop to Mercy Otis Warren.

- What does a letter convey that a ledger account doesn’t, and vice versa?

- Who is the audience for each source?

- What is the purpose of each source?

- What do they have in common? What differences do they have?

Proclamation of General Howe, 28 October 1776

- What is General Gage asking Bostonians to do?

- What is he offering them in return for their assistance?

- What do the Bostonian loyalists say it is their duty to do?

- How do these loyalists say they are different from the rebels, who are “of different Characters and Sentiments”?

- Historical Context: Why is General Gage currently asking for additional support from Bostonians? What is he concerned about for the winter?

Peter Edes diary, June-October 1775

- How does Edes feel about the British soldiers who captured and imprisoned him? What are some words that Edes uses to describe them?

- How is Edes treated in prison? What are some of the things he complains about?

- What is Edes eventually charged with as a crime?

- Who is the preacher Mr. Morrison, and what does he say about the people of Boston who rebelled?

- How long is Eden imprisoned in total?

Letter from Hannah Winthrop to Mercy Otis Warren, 8 July 1776

- How does Hannah Winthrop describe the damage done by soldiers to her house in Cambridge?

- According to Winthrop, how have things improved in Cambridge since the British left? List three examples.

- Now that they are no longer under siege, what is Winthrop’s biggest concern right now?

- Compare this ledger to the Account of damages done to Jonathan Green during the Siege.

- When looking at property that has been stolen or damaged, what does a letter convey that a ledger account doesn’t, and vice versa?

- Who is the audience for each source?

- What is the purpose of each source?

- What do they have in common? What differences do they have?

Suggested Activities

-

Introducing the Siege of Boston

-

Begin by asking students to share what they know about the Battles of Lexington and Concord.

Using the Historical Background, share an overview of the Siege of Boston, which began after Lexington and Concord.

Option 1: Read Aloud, Define Later. Present the text as a handout or slideshow and read aloud with students, asking them to glean what they can from the text and try to determine overall intent. Then review the vocabulary word by word.

Option 2: Begin by reviewing essential vocabulary (see below). Then present the information in the following text as a mini-lecture, and check in with students call-and-response style, asking them to summarize the information back to you.

-

VTS (Visual Thinking Strategies) with Relief Ellery’s teaspoons

-

This activity can be used as a bellringer to introduce the Siege of Boston. Present students with the image of Relief Ellery’s teaspoons, with no title or other clarifying information. Using the VTS method, ask students the following questions:

- What's going on in this image?

- What do you see that makes you say that?

- What more can we find?

After students have brainstormed, ask them what these spoons might have to do with the Siege of Boston–these spoons tell the story of Ellery’s experience of the Siege and wartime in Boston.

Extension: Ask students if there is anything that they or their family own which tells an important story? Students can draw a picture of the item and share.

Note: Teacher should NOT ask students what item they would take with them in a similar wartime situation. Although role playing is a powerful tool in social studies instruction, it is not emotionally safe for students in this context. In the same vein, teacher should avoid specifying that students identify an item that has been passed down in their family–such items may or may not be available to students. See our Additional Resources tab for more resources on teaching students who may have experienced trauma or displacement.

-

Question Formulation Technique (QFT)

-

Using a single image of a primary source (and potentially a caption), invite students to generate as many questions as they can using the Question Formulation Technique. Suggested primary sources for this activity: Relief Ellery’s teaspoons; Plan of Boston and its Environs map; Permit to pass through British lines; Prospect Hill/Bunker Hill handbill.

-

Mapping the Siege of Boston

-

In pairs, ask students to explore the Plan of Boston and its Environs map of Boston. Ask groups to fill out the following form together:

What can you find? Yes No Compass Legend/key Title of Map Name of Mapmaker Any extra decorations or images Source: the Leventhal Map Center

After finding these items, ask students in pairs to begin a KLW chart about the Siege of Boston. What do they Know, Learn, and Wonder about Siege after examining this map? Have students share their answers with the class.

As a class, examine the map in four quadrants. Have students do close observations. What do students notice in each section of the map?

A few highlights to consider:

- How was the geography of Boston different in the 1700s from the city they know today? What looks similar and different?

- Extension opportunity: compare the Plan of Boston and its Environs to a contemporary map of Boston or to Google Maps.

- Highlight the Boston peninsula and Charlestown peninsulas identified in the introductory reading. How might the geography of Boston have played a role in the Siege? How could people enter or exit the city? How would they get supplies?

- What can this map tell us about what the Siege might have been like for people living in Boston? In Dorchester? In Charlestown? What challenges would they have faced? What could they see happening in their towns or neighborhoods?

In their pairs, have students revisit their KLW charts by drawing a line under their previous answers. After the four quadrants exercise, what more do they Know, Learn, and Wonder about the Siege after reading the map more closely? Discuss responses as a class.

- How was the geography of Boston different in the 1700s from the city they know today? What looks similar and different?

-

Experiencing the Siege of Boston: First-Hand Accounts Jigsaw

-

Students can read an account in small groups as part of a Jigsaw activity (resources on Jigsaws here and here) and then fill out this worksheet. After completing their reading and group work, students should compare their answers and see whether they can find any common themes in their accounts.

Adaptations: Students can all read the same account in small groups, or the class can read an account out loud together.

Materials needed:

First-Hand Accounts

- Sarah Deming Account

- John Andrews

-

Originals: 6 May 1775, 1 June 1775, 11 April 1776 (transcription only)

-

- Hannah Winthrop

- Peter Edes

Worksheet:

Activity Worksheet: Experiencing the Siege of Boston

As a class, revisit the essential question: “How did ordinary Bostonians experience the Siege of Boston?” Encourage students to compare and contrast the differences and similarities in how different Bostonians experienced the Siege, and what factors led to those differences. What were their concerns, motivations, and fears living through wartime?

This lesson touches on themes of living through wartime or as a refugee, and this might be an opportunity for extension and connection to current events. Students may relate to this theme, but it could also touch on sensitive topics for some, particularly if any of your students or their families are refugees. Be sure to make sharing and participation optional when discussing these topics. For additional resources on teaching students who have experienced wartime or displacement, visit our Additional Resources Tab.

Extension Map Activity: Ask students to identify locations on the Plan of Boston and its Environs map related to the primary sources they read. For example, the only way Sarah Deming could leave Boston was via the Boston Neck, which had multiple lines of defense across it.

-

Experiencing the Siege of Boston: Quote Comparison Chart

-

Materials:

Experiencing the Siege of Boston: Comparison Chart

In this activity, students will use this comparison chart worksheet to examine short quotes from first-hand accounts of the Siege of Boston and explore common themes in the writers’ experiences.

-

Escape from Boston

-

Materials:

Worksheet: Journal of Sally Deming, 1775: Escape from Boston

Using this worksheet and the accompanying map, students trace the Deming family escape from Boston at the beginning of the Siege, and follow them on their journey across Massachusetts and into Rhode Island and Connecticut. Students also explore the story of Lucinda, a young woman enslaved by the Demings, and how her experience of the escape differed from her enslavers.

-

Wartime Propaganda

-

Materials:

This activity introduces students to the Prospect Hill/Bunker Hill Handbill from 1775, a piece of colonial propaganda that claimed that life was much better with the Americans on Prospect Hill than for the British on Bunker Hill. Their handbill argues that the Americans had better food, better pay, and better health, and it tries to convince British soldiers to desert their army and join the colonists instead.

Using this worksheet, ask students to imagine they are British soldiers and need to create their own propaganda to encourage colonial soldiers to desert and join the British army. What would they say? Students can try to think of realistic examples (such as arguing that the British army has better uniforms and weapons; the British army is larger and more experienced; colonists should be loyal to the British government), or they can be creative–the wilder the arguments the better!

Applicable Standards

-

C3 Framework for Social Studies Standards

-

D2.His.6.K-2. Compare different accounts of the same historical event.

D2.His.10.3-5. Compare information provided by different historical sources about the past.

D2.His.4.9-12. Analyze complex and interacting factors that influenced the perspectives of people during different historical eras.

D2.His.12.3-5. Generate questions about multiple historical sources and their relationships to particular historical events and developments.

D2.His.6.3-5. Describe how people’s perspectives shaped the historical sources they created.

D2.His.16.9-12. Integrate evidence from multiple relevant historical sources and interpretations into a reasoned argument about the past.

-

MA HSS and ELA Standards

-

Practice Standards

Develop focused questions or problem statements and conduct inquiries

Organize information and data from multiple primary and secondary sources.

Analyze the purpose and point of view of each source; distinguish opinion from fact.

Evaluate the credibility, accuracy, and relevance of each source.

Content Standards

Grade 3, Topic 6. Massachusetts in the 18th century through the American Revolution

Grade 5, Topic 2. Reasons for revolution, the Revolutionary War, and the formation of government

USH 1, Topic 1. Origins of the Revolution and the Constitution

ELA Standards

College and Career Readiness Anchor Standards for Reading

Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas.

Assess how point of view or purpose shapes the content and style of a text

Additional Resources

Ordinary Civilians and the Siege of Boston

Additional Primary Sources

-

Other digitized primary sources at MHS on the Siege of Boston

-

The image used in the header of this source set is ink and watercolor and was created in 1775. This four-panel panoramic view of Boston from Beacon Hill shows the line and encampments of the American and British troops as seen by a British officer during the siege of 1775. Included is a numeric key to major locations. Zoom in to see details.

This website presents more than one dozen accounts written by individuals personally engaged in or affected by the Siege, including soldiers, prisoners (one imprisoned Loyalist and one Patriot), and residents along with the record of a town meeting during the Siege. These first-hand experiences recounted in 25 manuscripts and associated maps and documents, give the human side of the American Revolution, a perspective often overlooked in histories that describe the Siege as a series of military events.

Letter from John Andrews to William Barrell, 1 June 1775

In this letter, which follows the previous letter in the source set from May 1775, John Andrews continues to describe conditions in Boston under siege. He details the struggles of various family members as they left Massachusetts in early May and his struggles to survive by himself in Boston given the shortage of provisions, and general insecurity over the military activities. Andrews remained at his residence in Boston to ensure that his family's belongings were not stolen by the British troops. Andrews tells Barrell that those that leave the town "forfeit all the effects they leave behind."

John Andrews to William Barrow, 11 April 1776

This primary source is not yet digitized, but the transcription is currently available. In this third letter from John Andrews, Andrews rejoices over the end of the siege and describes the evacuation of British soldiers and the harsh conditions suffered during the course of the siege. Despite the hardships, Andrews tells his brother-in-law, ”I never suffer’d the least depression fo spirits…for a perswasion, that my country would eventually prevail, kept up my spirits, and never suffer'd my hopes to fail.”

Broadside announcing permits in and out of Boston, 30 April 1776

This broadside announces the official agreement, made between General Gage and the Provincial Congress, allowing civilians to enter and exit Boston without harm while the town is occupied by British soldiers. Following the battles of Lexington and Concord, 12-13 thousand people fled Boston as a result of this agreement using passes under this agreement, such as this one in our source set.

To John Hancock, Map of the Seat of Civil War in America, 1775

This map by Bernard Romans, a former British officer who joined the American cause, was the first map printed in America to depict Massachusetts as an independent state. Although inaccurate in some local geographical details, the map served its purpose of graphically conveying the sites of Revolutionary War battles to the rest of the colonies. When presented with Sarah Deming’s account of the Siege of Boston, it can be used to identify locations she passed through during her flight from Boston.

Digitized resources at external institutions

This article compiles a number of primary source accounts, including many from this source set, to give an overview of civilian experiences during the siege.

American Battlefield Trust, The Siege of Boston, by Adam E. Zielinski

This article offers a detailed overview of the events of the Siege of Boston with a focus on significant military and political events.

Teaching the Siege of Boston with students who have experienced war or displacement

This primary source set touches on themes of living through wartime, forced displacement, and being a refugee. Students may relate to this theme, but it could also touch on sensitive topics for some. Be sure to make sharing and participation optional when discussing these topics.

Below are some additional resources for teaching students who have experienced war and persecution, displacement, flight and migration:

-

UNHCR (UN Refugee Agency): Teaching about Refugees (includes resources to support refugee students in the classroom)

-

Colorín Colorado: How to support refugee students in your school community